Good people make bad decisions because they have bad assumptions or limiting beliefs. If a leader has an assumption that trusting is bad, then they’re bound to make a bad decision because there’s no one there to stop them from making that decision. And once that decision is made, the decision-maker will look for any evidence to support that decision. They are tricking their mind to think that they are right. And, that’s how businesses crumble to the ground. Join Dr. Patty Ann Tublin as she talks with Dr. Alan Barnard (https://dralanbarnard.com/), entrepreneur, philanthropist, strategy advisor, research scientist, app developer, author, coach, lecturer, podcaster, and lifelong learner. They talk about the decision making process and why people make bad decisions. Learn more about constraints and how to solve them. Discover how assumptions affect decision making. Find out why people learn from experiments, not experience. And know the formula for measuring productivity. Start making the right decisions today by listening to this episode.

—

Listen to the podcast here

The Tricky Art Of Decision Making: Why Good People Can Still Make Bad Decisions With Dr. Alan Barnard

In this episode, I have a certifiable genius as our guest. You do not have to worry about being the smartest person reading this because this man is going to set your world on fire. Before we go any further, make sure you like, comment, share and subscribe to this show. Our guest in this episode is a true visionary and thought leader. His research focuses on why good people make and often repeat bad decisions and how you can avoid doing this.

We all have a laundry list of people that we know need this information. Dr. Alan Barnard is the CEO of Goldratt Research Labs, which he co-founded with Dr. Eli Goldratt. He also is a creator of the Theory of Constraints and the author of a book called The Goal. I’m going to have Dr. Alan share all of this with you. If I were to spend the time sharing with you all of his awards, we would be here until tomorrow. Suffice it to say that Dr. Alan Barnard is truly one of the smartest people you will ever meet. He is also one of the kindest and the most humble person you ever met. Put on your seatbelt because Dr. Alan Barnard is about to take us for a ride. Welcome and thank you so much for being willing to share your wisdom with us.

Thank you so much and thank you for the invitation. I’m looking forward to this discussion.

Tell us, what the Theory of Constraint is, but say it for people that aren’t half as smart as you so that someone like myself can understand it. I have heard you explain it before and I’m like, “It is hard to keep up.” For the average lady and gentleman, share with us what that is.

If you think about going to analyze a system or try to manage a system or improve a system, one way of doing that, is you talk to analyze, improve and manage each of the parts of the system. Whether you are dealing with a for-profit company or a for-purpose company and it’s made up of many parts. You can talk to analyze, improve and manage each of the parts. Unfortunately, that doesn’t give you the best possible performance. Is there an alternative way? The Theory of Constraints provides a very simple solution to that problem. It says that if you can identify what the constraint is of a system, the part that you don’t have enough of to meet the goal that you have set for that organizational company.

Is the constraint the part you don’t have enough of as opposed to what’s holding you back?

Yes. It’s a slightly different definition and it’s important to differentiate. If you set yourself a goal for your company, a for-profit goal or for-purpose goal like to impact a million people or to make $10 million and that’s your goal. That immediately dictates what resources you are going to need and what work you have to do to provide the products or services to meet that goal.

Any of those resources that you don’t have enough of to meet the goal is a constraint. If you don’t have enough demand for your product or service to meet your goal, that is your constraint. You might have enough demand, but you don’t have enough capacity to deliver the product or service and that becomes your constraint. Also, you might not have enough supply or enough cash. What the Theory of Constraints says is it’s like the analogy of the weakest link in a chain.

If you want to strengthen the chain, find the weakest link and strengthen that because by strengthening the weakest link, improving the constraint helps you to improve the whole system. It’s like a hack. It is, “How do I find this one thing?” One way of finding that one thing is by looking for the constraint and then focusing all your attention and limited resources on improving that part until the constraint moves. That is what the Theory of Constraints is. It gives you a systematic way of improving any system.

It says, “Define your goal.” If you haven’t done it, that should be your one thing. What is your goal and then to say, “Identify the constraint? What don’t you have enough of to meet that goal? Is it demand, capacity, supply, or cash?” Step two says, “How do I better exploit that constraint and not waste it? How do I get more from it?”

If it is demand, it might mean, “What market share do you have?” “I have 5%.” There’s 95% that’s available. What are those conditions that if you could satisfy them, would get existing customers to be willing to pay more, buy more, and buy more frequently? It’s the type of thing that Jay Abraham talks about. Whereas if it’s an internal capacity constraint, let’s say your sales team. You don’t have enough salespeople. Do the same thing. Decide not to then exploit and not waste it. How much time are they wasting traveling and spending in meetings? How can we get more out of it? That’s what step two is all about. It’s using what you have got better and then lifting up your performance.

Step three is subordinate everything to that decision. Any policy or process that you have inside of the organization that’s in conflict with a decision on how to better exploit it. You might have an internal policy that says, “No new hires. Our profit margins are a little bit under pressure. We are not going to hire more people,” but what if your constraint was salespeople? By hiring one more salesperson, you can increase the sales for the whole company by 20% and the cost will only go up by 2%.

That’s an example of step three of the focusing steps of the Theory of Constraints is to subordinate everything to that decision, you will have to change that rule to be aligned with where the constraint is. If that doesn’t give you enough to get to the goal, you go to step four which says, “Elevate the constraint.” Now, go and get more. Hire more salespeople, add more products and go into new markets. Step five says, “Don’t let inertia become the constraint. You want to continuously improve. Go back to step one.” Where’s the next constraint? Where is it going to move?

Give us a real-life example of how you are applying the Theory of Constraint to help a company grow.

I have worked with a Fortune 500 company. They are in a fortunate position at the moment where they can sell whatever they produce. If you think about that, as soon as I tell you that information, they can sell whatever they can produce. You know that their constraint is not in the market. The constraint is either internal. They have a capacity problem or they don’t have enough supply. It’s something that they need from the outside, either raw materials, components or it could be cash.

The next question I asked them is, “Do you have enough capacity to meet the demand?” If they said, “No, we don’t. We have enough supply and cash, but we don’t have enough capacity.” It’s internal. Where is your bottleneck? It’s internal in operations. I gave me this one area that they are using to develop this product that I have. That’s where the bottleneck is. You say, “Now, we know where your constraint is.”

If we can increase that resource by 20%, you will be able to produce 20% more and your whole revenues will go up by 20%. That will have a huge impact on your bottom line. It’s applying that, “Decide how to better exploit that constraint and not waste it.” We look for cases where that resource was starved or blocked or working on things that it shouldn’t be working on because we want to stop doing that or working on bad quality stuff. Every time we can correct one of those mistakes, it lifts up its performance. Normally, the first thing to do is to stop that resource from doing things it shouldn’t be doing. It’s what we call overproduction. By the way, for the readers, most likely if you run a small business, you are the constraint. Your limited attention is the constraint.

How do you solve that if you are a small business owner?

If you run a small business, you are the constraint. Your limited attention is the constraint.

The first thing that you want to do and probably most good coaches will tell you that is write down all the things that are demanding your attention and see which one of those things you should stop immediately because it’s not helping you achieve your goal. The remaining things on the list are, what can you outsource? What can you delegate? It’s so you are only focusing on those few things and then you will see immediately your productivity increases. As a result, your business growth will increase.

Those are two extreme examples. One way, you can apply to a Fortune 500 company, and the other way, you can apply to a single-person company but the principle is the same. At any point in time, there’s only one weakest link. There’s only one resource that is your constraint. Now, it could be that sometimes you make your goal so ambitious that you don’t have enough of anything. You don’t have enough customers, capacity, cash, and supply. The advice that is a little bit counterintuitive is to reduce your goal to the level where only one thing becomes a constraint because that allows you then to focus on that one thing.

As a summary of what the Theory of Constraints is, you mentioned that I cofounded the company with Dr. Eli Goldratt. He was once asked, how would you summarize the Theory of Constraints? He said, “I can do it with only one word, focus.” Focus doesn’t only mean knowing what to do. Much more importantly, it means knowing what not to do.

For you to be able to assess that, knowing what not to do means what parts of my system are good enough. That’s a hard thing for entrepreneurs to understand that there’s a level of good enough. You are going to invest $50,000 in designing a new website. Is that a constraint right to profitable growth? You can taste it if you wanted to. Invest the $50,000 and see if your sales and profitability go up. If it didn’t, you know that you improved the part that wasn’t the weakest link or the constraint. It’s better to ask yourself that question. As a fourth experiment first, is this my constraint? The fact that I can improve it is not important. I can improve every part. It’s figuring out what I have to improve to get more of the goals that are important to me.

Focus on letting the one thing be the one thing. Here’s a question for you. As a person that’s a relationship expert in businesses and personal relationships. This is a show on trust and relationships in business. What happens or what do you do when the bottleneck is the relationship or is the person or the teams aren’t playing nice in the sandbox? This is what I do a lot of or the co-founders aren’t getting along or the CEO and the COO are no longer aligned. What happens when you are working with those types of issues that you can’t put your finger on?

I would say the first thing is we have talked to differentiate between a challenge or problem versus a constraint. They are not the same thing. As I mentioned, a constraint is something. It’s a scarce resource that I don’t have enough of. Now, there are few scarce resources when it comes to human beings. Most people, if you ask them, what don’t you have enough of to achieve your goal? They will tell you, “I don’t have enough time, money, knowledge, or experience,” but those are not scarce resources. The scarcest resource we have, number one, is attention. The things that demand your attention will always exceed your available attention.

Is it attention not meaning your time, but attention meaning your focus?

Attention is focused time. I’d like to call it the time that you have every day to make meaningful progress towards the goals that are important to you.

That would be a differentiator. You put your attention to anything that will move the needle.

Think about this how much attention do you have available now? There’s a lot of stuff that we go through on automatic mode and most people will tell you, it’s probably just 1 or 2 hours every day. There’s a lot of noise where I can sit and focus my attention on the things that matter. Your first personal constraint is attention.

The second one is motivation. That’s also a resource that we have that is a limited supply. I have to fill up my bucket of energy or motivation by doing things and being with people that support me and close that bottom out of my bucket, the things and people are drying it. That’s also a scarce resource that I have to manage and allocate it very wisely. The first one to me was very interesting is that it turns out that trust is also a constraint. We have very limited trust.

Trust is an accelerator in a company.

It’s also a scarce resource and the reason how we know that is you have to allocate trust. Like anything, I have to decide what and to whom to allocate.

It’s where you place your trust.

If you think about it, our default mode is not to trust.

It’s an untrusting world.

The two mistakes that we make when it comes to the allocation of trust are first, we trust people that we shouldn’t and that’s pretty bad.

That’s when smart people make bad decisions.

The worst mistake you can make is not trusting somebody that you should have because that takes away opportunity.

We trust people that we shouldn’t. You get into a relationship business or romantic relationship but there were a bunch of red flags. You were on a honeymoon phase and you ignored it, and then now you are stuck. It turns out that it’s not the worst mistake that we can make. The worst mistake we can make is not trusting somebody that we should have.

That’s trustworthy.

If you are an organization, you have to trust the people with that you work. If you don’t trust them, basically what the mind does is constantly looking for evidence to support your belief. When you distrust everybody around you, you are constantly gathering evidence to support that belief.

That they’re not trustworthy.

You will then get into a vicious cycle that’s impossible to escape from. That’s my advice as to view trust also as a constraint to realize you have to be very careful how you allocate trust, to what, and to whom, but that the biggest mistake is not trusting somebody that you shouldn’t because the worst case is you lose some time. The biggest mistake is not trusting people that you should have and not trusting things that you should have that take away opportunity.

My understanding and this comes from Stephen M.R. Covey’s book Trust & Inspire or maybe it was before that. What he talks about is smart trust. I worked with this all the time. He at least gave me the framework on how to speak about it. When you have smart trust, it’s based on two things, especially in an organization. It’s competency and character. Oftentimes, the competency, everybody’s played pretty clear on that. That guy can do the job. Stay away from that person. He can’t do the job, but it’s the character piece that gets you into trouble.

In your theory of constraint and I know I’m asking to play in my field, but we all deal with human behavior. We also talk about the older generations’ thoughts that trust should be earned. The younger generation thinks trust should be given, which is what you are saying. Trust until somebody proves otherwise they shouldn’t be trusted, but smart trust. You don’t get somebody that can add up the CFO position because you trust them or like them.

You might also have somebody that’s brilliant, but their character is a little sketchy. I don’t want them to be my CFO either. It’s a very basic example. How do you, in the theory of constraint or maybe there’s a better way you can speak about it, address that knowing that trust because I think trust is at the heart of every successful business relationship? How does that work into the Theory of Constraint if you don’t have enough of it? If you don’t realize you are giving your trust to the wrong person, even when other people tell you, “Are you crazy,” or they won’t because there’s an issue of trust in the organization and then people will not speak the truth to power.

I think it starts with what your starting assumption is. Most people think that the starting assumption is that trust should be earned and that it’s better, you will be more protected by not trusting and letting people earn their trust. It’s old school, but it’s also flawed. Part of the reason I explained how our human mind works are it’s constantly gathering evidence for what we believe. If you start with a belief that the other side cannot be trusted, you will constantly look for evidence to support that belief.

Guess what will happen if you don’t find the evidence? You don’t go, “I was wrong all the time.” You will look for more evidence. You will think, “They hiding it well,” or you start changing your threshold or your standard. Suddenly, them telling you a white lie about why they were late for the meeting is not evidence that they cannot be trusted. They are lying and now you feel much better. We understand why people do it, but it’s not a good starting assumption. As you said, a better starting assumption is to make me trust you until you prove me wrong.

That means that I need to be careful of those red flags. I need to write down one of those things that I should look for and get fast feedback on it. If I get into a relationship, either a business relationship or a romantic relationship, I want fast feedback loops. I don’t want to wait for twenty years to find out, “I want to be able to know that wasn’t the first thing we do,” but that’s sometimes what happens.

This is a perfect segment for the next question but the readers know this is all organic. It’s not like we rehearsed this, but I’m thinking about the work that you do. The issue though with the trust, this is the caveat and then I will go to my question. The higher trust in an organization, the quicker people will present to you an issue. There’s an issue of somebody’s screwing up. They will come to you right away but when it’s a low-trust organization, there’s more of a lag time between when the situation happens and when it comes to light.

Many times, it comes to light by somebody else outside the organization, like the front page of The New York Times and it’s usually not pretty right or a best friend’s friend tells us if somebody’s fooling around on us. With that understanding of low trust organization, the lag time between feedback and high trust organization happens right away. Explain how that can help us understand the concept of when understanding why good people make and repeat bad decisions. I’m hearing it connected unless I’m just complicating things.

The simple answer to that question is good people make bad decisions not because they are bad people, not because they are ignorant, but because they have bad assumptions. Good people make bad decisions for good reasons. What are the good reasons? Mostly, it’s because they have some bad assumptions, some limiting assumptions, or beliefs. For example, it’s better to not trust. That’s a bad assumption. It will have an impact on the culture that you create.

As a leader, you have to flip that around. If you want to create a culture where they are stressed, you have to show trust to others. You have to give them fast feedback about what’s happening and the financial status of the company. A couple of years back, I was sitting down brainstorming with the CEO of a very large company and he said that one of the biggest frustrations he’s got is why do people not speak up when they make a mistake. I said, “Why do you think?” It’s because they are scared.

Did he ask what were they afraid of or did he know what you were talking about?

No, he immediately knew. In a corporate environment and it’s interesting logic. People are more scared of errors of commission doing something that they shouldn’t than errors of omission, like not doing something that they should.

It’s the reason why low-trust organizations have little innovation.

The only protection you have against being held accountable for a bad decision is to immediately share that bad decision.

I said to him, “Here’s what we’re going to do.” We are going to have a one-day workshop and you are going to send out an invite to sell that we launching a competition. We are launching a competition to see who can claim that they have made the biggest mistake that’s cost the company the most money. He said, “Nobody will apply for the competition.” I said, “You have to say that you are going to be competing as well and you suspect that your mistake was ten times worse than anybody else’s mistake.”

Why you are launching the competition is we have to learn from experience so every mistake that’s shared, we are going to try to understand what was that good reason why that mistake was made which essentially was the bad assumption at the time. How can we make sure that we never make this mistake again? We will publish this as a booklet of case studies. This will be the start of the journey where we are encouraging people to share immediately the mistake that they have made, why and what they have learned from it and that’s the thing that gets you off the hook.

It’s your permission to fail.

We don’t want to learn fast from failures. We only want to learn fast. The sooner we learn from it, the better. We had this day and it was fantastic. It was so interesting because he stood up and he said, “I had decided to outsource this thing. I outsourced it to a competitor. There was a massive burndown in one of the factories. Suddenly, we were completely dependent on them to supply. With the short supply, the price doubled. It wiped out all of our profits and it costs us hundreds of millions of dollars.” I’m quite confident that during the whole day, nobody will share a bigger mistake.

Was that a true story?

Absolutely and it was fantastic because it was like this cloud that lifted off people and everybody had that, “Suddenly, I can tell them.” We encourage them to share everything including one of the biggest reasons for bad decisions as again, not because of bad people or ignorant people, but because of bad measurements. Show me how you measure me and I will show you how to behave. If you measure me on the wrong thing, don’t be surprised at my behavior. We ask the same question to people. Are there situations where you are taking an action that you know is bad for the system, but you feel compelled because of the way that you are measured?

It happens all the time. I worked corporate and I’m an entrepreneur and the whole quarterly pressure is out of control. It is so bad.

I think that’s a short answer to your question trust is important but it has to come from the top.

That’s where the culture permeates from. What were the tangibles that changed in that company when that exercise was done?

The first thing was that we wanted to measure the lag between the mistake being made and that mistake being announced and that dropped dramatically. Essentially, what we said is that the only protection you have against being held accountable for a bad decision is immediately sharing that decision. As soon as you get evidence that the consequences were bad, share it. That’s important because a bad decision and a bad outcome are not the same things.

You could have a good decision that has a bad outcome and you could have a bad decision that has a good outcome. For example, I can decide that even though I’d had three glasses of wine, I feel okay to drive home. I get home and I’m safe. Was it a good decision? No, it was a terrible decision. You could have killed somebody and destroyed their life and your life. That’s the other thing that we teach in the organization is to be careful. A good and bad decision doesn’t mean a good or bad outcome.

You can have a good decision that resulted in a bad outcome simply because of probabilities. It’s that in most cases, that decision would have resulted in a good outcome, but sometimes it could result in a bad outcome. We launched a new product. We fully expected that sales went up. It didn’t go up. Now, we want to know why. The sooner I declare the bad outcome, the sooner I can start analyzing to see what the bad assumption was that we made.

I think you are mature enough to remember the years ago when Coke launched that disastrous new Coke product. I’m in Stanford, Connecticut and here you have a company with a lot of smart people. They spent a lot of money on marketing dollars and it was an absolute unmitigated flop. I assume that was from bad assumptions. This happens on all different scales. How does that happen in an organization?

What we know from the way that our mind works, as I mentioned, is we don’t rationalize and then we decide. We decide and then we rationalized. We make a decision and then we look for evidence to support the decision. It’s quite hard to disprove yourself. It takes effort. What happened, in that case, is they decided that by changing the taste of Coke, they will be able to better compete with Pepsi because Pepsi was killing them in the blind tasting taste.

They decided to come up with that and what they did was they had focus groups that in hindsight, what it looks like is they were blind to the evidence. There was a significant amount of people that hate it because they believe this is better. You now look at the focus group data and you look for evidence to support your conclusion. In hindsight, if the focus group was saying, “We don’t know if this has been or not.” That’s the purpose of doing the experiment. It’s to check if it’s going to work or not work. You have to make it falsifiable.

That’s one of the criteria for the scientific method. Anything that science is, you asked to be able to do an experiment that can tell you if it didn’t work, that your hypothesis is untrue. I think the same is true for anything. We think that something will work so we look for evidence. We think that we shouldn’t trust somebody so we look for evidence. The way we always have that bias and when we are designing an experiment, we should design it in a way that we can taste. My biggest conclusion is that we don’t learn from experience. That’s why we don’t look. That’s why we often repeat mistakes. Why is that? While we don’t learn from experience, we learn from experiments.

Tell us more about that.

An experiment where the assumption is very explicit and I have a way of validating or invalidating it and then I can get fast feedback. Imagine touching a hot stove plate. Why does it normally take only one place to learn? It’s because you get immediate feedback. Imagine if that hot stove burned you a day, week, or a month later? That’s a challenge that people have in an organization is the lag between the action and the consequences is often quite significant.

People do not learn from experience, they learn from experiments.

That is exactly why for years, they had stock performance and executive pay tied to the stock performance but the ramifications for the bad decisions 2 or 3 years later, but they took their money.

That’s the key thing is whatever assumption you want to try out or taste, you have to design an experiment where that assumption is very clear. If it’s about, “We can trust these people.” How do I design an experiment to know whether I can trust them, yes or no? How would a person behave that can be trusted versus who cannot be trusted? Also, how can we get quick feedback about whether that’s taking place? As I mentioned, as soon as you trust somebody, you start looking for evidence to trust them.

If you decide not to trust them, you look for evidence not to trust them. You want to say it’s a good starting assumption to trust, but I have to do smart trust. I have to be explicit and make it foolproof. To me, the best way to operate is to create situations where people do not require trust. That there’s only one way of doing things and that’s the right way of doing things.

I’m going to push back, which is probably going to get me into so much trouble, you truly are a certifiable genius but from what I remember from my science and doctoral days, there is an objective experiment because human by definition brings their subjective perception but it’s the whole conversation about AI. You still have to create it. There’s an inherent bias that gets put into the formula of the person creating whatever it is.

If there’s an experiment and based on my life experience and my perception of what I think is the truth, it might be different than yours for many reasons. I’m a woman. You’re a man. I’m an American. You are from South Africa. Two different cultures and genders. I bet you we have had two different life experiences up until even right now. With that being said with the limitation of humans, not being able to be completely objective, which I think is the beauty of human nature, how do you account for that or maybe I’m just too simple to understand that?

No, I think it’s a great point. One of the things that you realize when you start studying science, that’s the first thing that they drill into your mind is that you can never prove yourself right, but you can prove yourself wrong. You can go in and do observations once as you do 1,000 observations and you come back and you say, “Every time I have looked for swans, they were always white.”

At what point can I say that all swans are white because the last 1,000 observations were all white swans? It only takes one observation of a black swan to crush that hypothesis. When you are thinking about doing an experiment to say, “By doing this, we think that customers will buy more,” or, “By doing this, we think that employees will become more productive or happier in their workplace.” Thus to say, can I design an experiment that can help me at least to the order of magnitude? Because many of these things I can’t measure precisely, I can normally measure at least three levels. Has it made it better or much better or has it might have been worse?

They call it statistically significant.

As a control limit, they say listen, within this portion, it’s noise. I don’t know. If I were interviewed now, I’d say, “We made this change a month ago. Do you feel happier now?” On Monday, you told me happily. On Tuesday, you tell me you are not so happy. It’s noise. I have to decide a way and often, it’s about asking the person, “What would you look for if we have made this change for you to know whether you feel more trusting in this company where you feel more productive? What are your criteria? How would you know, whether we’re getting better or much better, worse or much worse? It’s not a big change and it’s often just sitting down with them to say, “How are we going to measure whether this is an actual result of an improvement?”

If you have a huge company, can you ask every individual how they would measure success?

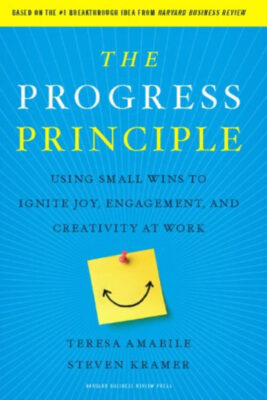

I don’t know if you have read the book The Progress Principle. That’s a good example of this type of experiment. They tried to understand what creates happiness in their organization. What makes people feel unhappy and happy? They asked the people through interviews and they ask their managers and what they found out was that they contain the same list but that, wasn’t the thing that made them happy because if they try to implement that, they don’t measurably improve happiness.

What I asked people to do was two things. I said, “On a daily basis in your diary, we want you to make a face like a happy, sad, or neutral face about how you feel. Secondly, we want to record any of the events that happened that day. That’s it and just do that for 30 days. They didn’t put the data together. I found some interesting correlations and found out that what is key to happiness is that people feel they are making progress towards an important goal for them personally and for the company.

The idea of progress was important. It wasn’t so much about an absolute number. It’s what is that absolute number relates to from what it was yesterday and the day before. Are we going up, down, or staying about the same? Whenever we go up, it then makes me happier but there was a second requirement. Was that in the crisis where my performance has deteriorated that I expect a leadership team not to hold them accountable for it, but to ask, “How can we help?”

Once you have got them the help and they still don’t perform, then they failed to be held accountable. It turns out that those two were the big things is getting everybody to think about your performance that’s required. How do you make sure you don’t become the constraint? That your department always have enough resources? What are you going to be measuring? Is it the turnaround time of the applications that come in or the amount of stuff that you can do? We have this measurement that I have developed. It’s called QT/OE. It stands for Quality Throughput over Operating Expenses.

This is the base and simplest way of measuring productivity. If you think about what they represent, Q is the quality of your work and that’s dictated by your customers. You asked them, whether it’s internal or external, how will they measure the quality of work. The second thing is throughput. It’s how much work have you done? How many invoices that you completed? How many project tasks that you completed? How many tons that you produced? How many clients did you call?

That’s the throughput component. That output of your process. Also, there are operating expenses. All the costs that you have incurred to generate quality throughput. Essentially, it’s now a ratio and what’s important is not the absolute number. What’s important is what’s happening with that number over time. Throughput or output is limited by the amount of demand that you have for your department’s service.

The upper limit is, “I’m meeting all the demand,” and that becomes my upper limit of it. If you are not meeting all your demands, guess what your first focus area should be to improve your productivity? It is to find a way of getting capacity to meet all the demand. Once you meet all the demand, then you have to meet it according to the quality criteria of your customer. That’s the second leverage point for improving our productivity is increasing the quality but again, there’s an upper limit which is, whether it’s good enough.

That top line is the effectiveness component, quality throughput and output. Below the line is the efficiency component. What is the total cost for you to provide them? What you can see is if I make a trade-off, if I go and reduce operating expenses but it hurts either my quality, my throughout or my output, it will immediately hurt my productivity. I’m constantly looking for changes that I can make that give me a big upside.

Quality and output over operating expenses. This is the formula of measuring productivity.

It increases my quality and throughput more than it increases my cost. I’m then being productive. You can take any initiative in the company, whether it’s an initiative to improve the trust or to improve other areas of the business but that should be the ultimate metric that says, if this initiative was good for the organization, I should see a measurable improvement. I should see measurable progress in quality throughput over OpEx, QT/OE. It contains that ratio and it prevents people from local optimizing. If I measure these three things in isolation, I can spend a lot of money on quality, but it doesn’t help because my throughput doesn’t go up or I can tuck the resources and I’m not aware of the downside of that. Suddenly, I can’t meet my demand.

Let’s shift gears for a moment. Who is Dr. Alan Barnard and how did you get here? Who are you? Tell us a little bit about the man that you are and how you got here.

I was just very curious always about what makes certain people become successful. I grew up in South Africa. We don’t have many resources. My grandfather always encouraged me to study successful people and that made me curious. As soon as you think, “They became successful because they had better starting conditions than you. They were clever.”

That’s an assumption.

As you are reading this, you find out that most of the most successful people in the world often faced quite bad limiting conditions.

They were hungry for knowledge. Who was one of the first people that you studied that you were like, “A-ha?”

In our own family, a distant uncle of mine was Dr. Christiaan Barnard. He was the doctor that did the first heart transplant. If you looked at that and you say, would anybody put money that somebody from South Africa that grew up very poor, that had very limiting conditions in the hospitals, would they be the first one to do a heart transplant? There was a race going on all around the world. Some of the leading academic institutions in the US and Russia and everywhere else were trying. That to me was like, “How was it?” It turns out, it’s got very little to do with your starting conditions and much more to do with your starting assumptions.

I do want to hear about him. It’s an expression that a friend and I use all the time. It’s like, the guy was born on third base, but he acts like he hit a triple. That huge advantage and guess what, they never leave the third base. What was the condition of your distant cousin?

I realize that and this was shortly after I read this famous quote by Henry Ford where he said, “Whether you believe you can or can’t, you are right.” I thought, “Could that be the starting assumption that matters?” If I believe I’m not a good public speaker, I won’t even try.

Was Elon Musk originally from South Africa?

He was also. It’s the same thing. You can go and look at and say, “His parents are pretty impressive, but nothing out of the ordinary, yet this kid grew up with this compulsion that not only can do something but he has to do something. It’s a combination of those two things that I learned early on. It’s not just that you believe you can, but you believe you must.

Is it driven by a sense of, “To whom much is given, much is expected?” Meaning brainpower and you must, because this is your purpose in life or the world needs this. I mean this sincerely. It’s like the COVID vaccine. I know there was a template there already, but we got through a lot of the bureaucracy. We created a vaccine in four months or refined it and there was a sense of, “We have to.” We saved lives. I will even go so far as to say during World War II, America and its allies saved the world from fascism. We had to defeat it because it’s our way and the world is full of compulsion.

There’s that quote that says, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” Sometimes I think it is like that, but it often is not that. It’s often this curiosity. When I work with young people and they say, “How do I, how do I get to watch my life goal and my purpose? I asked them, “What bothers you?” If it’s about animal abuse, woman abuse or discrimination, or the fact that we wasting scarce resources, it bothers you because you feel responsible.

That you should be doing something. It wouldn’t bother you. You would treat it as if life is quite sad. A lot of bad things are happening. It only bothers you if you feel like you have to do something about it. I think that’s a good way of starting. Often, these great breakthroughs come from somebody who not only believes they can do something about it, but they must do something about it because they feel responsible and that can generate amazing insights.

It is a curiosity too and I know we have to go but I could talk to you forever. I would love a round two but I think the research shows that women are becoming entrepreneurs at double the rate of men and many times it’s because women, stay in need as part of their life. They feel there’s a need to do something like Mothers against drunk driving, from years ago.

Women also have a unique challenge from a decision-making perspective. One of my PhD students is working on this at the moment. She was curious about this inconsistency for over many years. Why so few positions are registered of women? Why a few of the top positions are occupied by a woman? The question is, can it be fully explained by discrimination and other things or is there something else at work?

I liked the way you are hedging that because I’m trying to figure out if I’m going to pounce on you or not.

What she is testing at the moment is that research shows that women make many more decisions than men every single day. We also are aware of another factor, which is called decision fatigue. The more decisions you make, the more fatigue you get and the more you are defaulting to a decision that is very low risk to you. A very simple thing is how much time and cognitive capacity women use in the morning to decide what to wear compared to men.

It’s not just that you believe you can, but you believe you must.

When you look at, “How do you overcome that?” Even men do that. Steve Jobs is like, “I have a standard outfit because I want to save this cognitive capacity and my willingness to tolerate the risk for where it matters. The more I can reduce those trivial decisions, the more I’m releasing capacity.” That’s the area that she’s exposed to.

It’s a very complex and very sensitive issue but I think that the basic assumption can provide some kind of explanation to say that for women to take risks, it’s much harder than for men. Part of that is not only our biology and genes, but part of it is because women tend to make many more decisions than men. You have to be even more careful about what are the things that you apply or thinking to do versus not.

Feel free to put that woman in touch with me. I would love to have a conversation with her. I think that that’s true. There’s the joke that if a man says, “I’m going to go to bed at night.” He gets up and goes to bed. A woman says she’s going to go to bed at night. She gets up, she takes the dishes out of the dishwashers. She takes the clothes out of the dryer. It is part of the decision fatigue. Having said that and I know you are talking about patents. I’m all for personal responsibility. I will not fall on the sword of, “Woe is me. I’m a woman.” I don’t agree with that. Having said that, the research also shows that venture capital is not given to women.

There is also a societal bias against women taking risks, not only coming from themselves but from the people that will allow them to take a risk for many different reasons. I do think it’s complicated, but I would dare say that women don’t have as many brilliant ideas. They just might not be patented. In an organization, a woman makes a suggestion and nobody listens. The guy says the same exact thing, not three seconds later, and he’s a genius. There’s a lot of stuff.

I will leave you with this quote. That to me is the exciting part of it because there’s this principle in science that says one case is sufficient. If I’m a person and I think that my starting conditions are limiting me from achieving any meaningful goals in life. All I have to do is to look for one case of somebody that was in the same position as I am that managed to achieve it. That’s all I need. I don’t need hundreds. I only need one case to show me that it’s possible. What we encourage people to do is this question of mine is, “How do you find and discover a limiting assumption?” To me, the most limiting assumption is if we start believing that it’s impossible. That something meaningful is impossible.

I simply challenge them to ask themselves, “It’s impossible, unless,” because what that does is it trips up the brain. It reboots the brain to start focusing on the conditions that could make the impossible possible. It’s a great disruptive question. It gets people out of that stuck mode that says you have a goal that’s so ambitious that you think is impossible. It’s impossible, unless and let them write the conditions. That becomes your plan. That becomes the conditions where the impossible becomes possible.

I love that because that brings us full circle because that identifies the constraints.

The bottleneck is always at the top of the bottle. I will leave your readers with that. It’s some limiting assumption of belief and it’s about how do I discover them? How do I challenge them? How do I design an experiment to go check if there may be a better way?

I know you have to run, but I have to ask you. What’s the last book you re-read and why?

I love Thinking, Fast and Slow by Dr. Daniel Kahneman who he talks about the two systems of thinking. System one, which is our fast and automatic mode, and then system two, which is a slower and more deliberate mode. What he talks about specifically in there is system one is prone to errors. We are making very predictable mistakes when we use our gut feeling, our instinct, and intuition. That’s why I’m always squeamish when coaches and mentors tell people when it comes to decision-making, “Just count down from 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and decide.”

No. If it’s a bloody important decision, take the time and slow down your thinking. Look at it from all sides. Look at it from all perspectives. Try to come up with as many options as you and pick those options that have a big upside if it works and a small downside if it doesn’t. Also, stay the hell away from those options that have a small upside if it works and a big downside if it doesn’t. I think that’s a simple framework for thinking about decision-making.

How can people find out more about you? Where would you like them to go?

My website is DrAlanBarnard.com. Our website for all of our decision support apps is HarmonyApps.com.

We didn’t get to it yet so we will have that in round two. Thank you so much. I talked about not feeling like the smartest person in the room like, “Wow.” That concludes this episode of the show, restoring trust and enriching, significant relationships. As I told you, Dr. Barnard did not disappoint and he took us for a ride. Make sure you like, comment, share and subscribe to this show. Until next time. Be well.

Important Links

- The Goal

- Trust & Inspire

- The Progress Principle

- Thinking, Fast and Slow

- https://DrAlanBarnard.com/

- https://GoldrattResearchlabs.com/

- https://HarmonyApps.com/

- https://TOCOdyssey.org/

- https://www.LinkedIn.com/in/dralanbarnard/

- https://www.Facebook.com/dralan.barnard

- https://www.Instagram.com/dralanbarnard

- https://Twitter.com/dralanbarnard

About Dr. Alan Barnard

Dr. Alan Barnard is an entrepreneur, philanthropist, strategy advisor, research scientist, app developer, author, coach, lecturer, podcaster, and lifelong learner. Alan is considered one of the world’s leading Decision Scientists and Theory of Constraints experts. Alan is the CEO of Goldratt Research Labs, which he co-founded with Dr. Eli Goldratt, creator of Theory of Constraints and author of THE GOAL.

Dr. Alan’s research focuses on understanding why good people make, and often repeat bad decisions, and how best to avoid these. From this research, Alan and his team at Goldratt Research Labs have developed the range of award-winning Harmony Apps that help organizations and individuals make better faster decisions when it really matters. GRL’s clients include Fortune 500 companies, Government Agencies, and people from over 70 countries that are using their apps to make difficult life and business decisions.